The Lviv pogrom

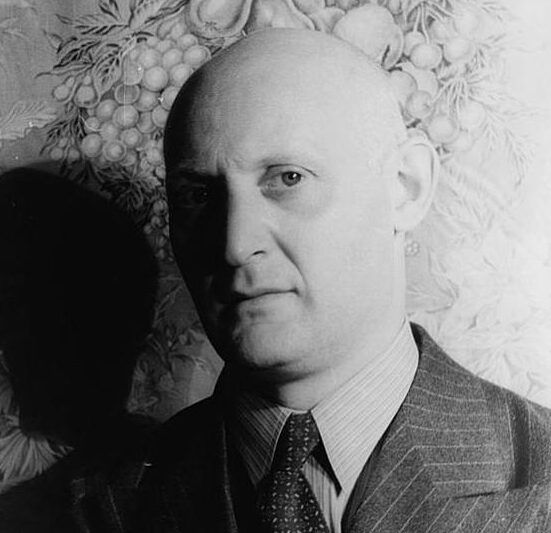

Pages from the novel The Ashkenazi brothers by Israel J. Singer (Ed D. Aprigliano)

The following pages are taken from the final part of the novel The Ashkenazi Brothers by Israel J. Singer, a Polish-Jewish author who lived between 1893 and 1944. It is a chapter dedicated to the Lviv pogrom of November 1918 by Polish legionnaires and Ukrainian civilians. We are at the end of the First World War, Germany has been defeated, the Russian Empire has fallen apart and Poland can finally assert itself as a nation. For this reason it contends with Ukraine for some territories.

From the self-determination of peoples to ultra-nationalist violence, however, the step is short, and the Jews, often experienced as a foreign body ensnared in the national body, are the first to pay the price, especially when looking for a scapegoat or wanting to vent repressed violence. This is how we move from nationalistic passion to anti-Semitic carnage.

Also for Felix Feldblum, for the revolutionary who had suffered so much for the liberation of Poland, in the certainty that a Poland freed from the foreign game would become an example of justice and equality for the rest of the world, the time had come for him too of the triumph. The crown of thorns that had stood on Poland's forehead for more than a hundred years had finally fallen. Krakow Cathedral, where the bones of Polish kings and poets rested, was no longer a barracks and stables for the Austrian cavalry. The Polish flag flew from the highest pinnacle, as in all other corners of the country. The young people of Kraków had formed a special legion which was now marching on the city of Lviv, to liberate it from the Ukrainians. Joined to that legion was the regiment in which Felix Feldblum had served first as a private and then as an officer. Sword swinging at his side, epaulettes resting crookedly across narrow, sagging shoulders, he now marched at the head of his troops. Behind, the men sang the hymn of the Crocuses, the name taken by the legionaries of Kraków.

General Roya on his steed,

at the head of the Crocuses he rides proud.

General Roya don't stop,

until only one Russian remains to be killed.

General Roya keeps marching,

until only one Jew remains to be killed.

The Jews of Lviv learned of the approach of the "Crocuses" and trembled; bad times had come, for them, and not only for them. Poland was full of refugees, of demobilized soldiers belonging to the most varied nations.

From the Ukraine, the Crimea, Volhynia, Podolia and White Russia, masses of disbanded Germans were trying to get back to Germany.

They crowded the trains, they clambered over the running boards and car roofs, but even so, there weren't enough trains to carry them.

They were a ragged and demoralized crowd, and they didn't know what tomorrow awaited them. Many had become revolutionaries and wore red cockades on their uniforms. Alsatian troops, hearing that Germany was liquidated, had proclaimed their allegiance to France and marched through the streets singing French hymns. The Poles of the Posen district, who had started the war as German soldiers, threw away their loyalty to Germany, and in bad Polish they began to sing Polish patriotic anthems. These "prodigal sons" were held in high esteem by the population, particularly by young women. They were given first places in churches and in popular processions. Even Austrian troops, belonging to all races of that multicolored empire, filled the streets of Poland. Their morale was even lower than that of the Germans. They had revolted against their officers, and had pillaged the stores of subsistence; they sold their uniforms and weapons for very little money. Each national group went back to its own language and pinned the emblem of liberty on the garments. Polish soldiers deserted en masse and joined Polish regiments; the Czechs removed the metallic emblems of the empire from the caps and replaced them with those of the new Czechoslovakia. The Hungarians also proclaimed their independence. The Bosniaks, the Romanians, the Slovenes, the Ruthenians, the Serbs, the Croats, all sang their hymns in their own language and all marched to their homeland. Only the Jews remained in their places, near their houses, their synagogues, their ancient cemeteries. But everywhere, in Jewish towns and villages, the walls were covered with posters announcing the impending storm. Schoolchildren of the recently liberated Polish state filled the walls with insolent and threatening graffiti. "Poland to the Poles," read the captions. “Jews go to Palestine. And if they don't, there's going to be trouble." Above the military marches that accompanied the processions in the cities, the sound of breaking glass from the stones being thrown at the houses of the Jews began to be heard. Most unfortunate of all were the Jews of Eastern Galicia, in the Lviv area. The towns and villages had been devastated by the Cossacks during the Russian invasion. Many Jews had been driven out of the province and some deported to Siberia.

A great famine had followed the invasion, and the famine had followed the plague. Jewish soldiers, enlisted among the Galician population in the armies of the Austrian Empire, returned home by the tens of thousands to find misery and desolation. According to widespread custom, many of these soldiers had pinned the Star of David on their uniforms. But their fellow soldiers kept mocking them. "Why don't you go to your country? We don't want you here." The older Jews did not want to hear about these symbols. They had enough of war and military emblems. They had had enough of the service, discipline and non-Jewish ways of life they had been forced to follow in the army.

When everything had collapsed, they began to grow locks again and resumed their old habits. They forgot the erect military gait, they returned to crowding the synagogues to pray and study as in the past.

The immemorial weight of Judaism, the double burden of this world and the world to come, rested again on their shoulders. They had to pick up the thread of their life where they had left it; they thought of the work tools left unused in the attics of their houses; the time had come to return to normality, to earn a living, bring up the children, educate them in Jewish life, marry the daughters, in short, the long, onerous, tiring routine they were used to. In the houses of study, in the Hasidic synagogues where they gathered, they sought comfort by raising their eyes to heaven, to the King of kings.

But their prayers were in vain. The world would not go back to the way it was before; war and violence would not cease. Other smaller wars broke out, consequences of ancient enmities, between the Poles and the Ruthenians, between the Polish nobles and the peasants. Each small group made claims to power. Now or never, they told themselves. And the Jews were caught between the contending parties; wherever they came from, the bullets went through the streets and houses of the Jews; each of the contending parties demanded the help of the Jews and charged them with treason if they refused to get involved in those disputes. The fiercest of these secondary wars was fought at Lviv. The city was held by two rival armies, the Polish and Ukrainian armies; each occupying his own area and firing at each other across the space between them, which was occupied by the Jews.

Young Jewish soldiers and officers of the former Austrian army organized a Jewish defense to repel the robbers and murderers who had begun to raid even in broad daylight. The Jews proclaimed themselves neutral between the Poles and the Ukrainians, hoping thereby to appease the eventual victor. But the Poles took this declaration of neutrality as an offense; and although the Polish command approved it and signed an official agreement with the Jewish defensive corps, a violent aversion to Jews spread among the troops, who were denounced as enemies of Poland. The low-strength Polish military menaced the Jews openly. "Wait and see!" they shouted. "When we've kicked the Ukrainians out, we'll teach you how to be neutral!" And they didn't fail to do so. When the Ukrainians withdrew from Lviv, Polish troops staged an attack on the Jewish Quarter, exactly as if it were an enemy fortress, rather than a defenseless area of a conquered city. And following the troops came a looting mob, clerks and nurses, thieves and prostitutes, prelates, monks and housewives, a motley crew that invaded the Jewish streets. "Down with the Jews!" they screamed. "Hang them by the beard!" Officers marched openly at the head of their troops, one officer for every ten soldiers. They surrounded the command of the Jewish defense corps, disarmed it; they shot the leaders and arrested all the men. And then the carnage and looting began. The attack was initiated with the precision of a battle. At seven o'clock on a cold November morning, Polish legionnaires surrounded Krakow Square with machine guns and armored cars. The outlets of Synagogue Street, Shulkev Street, Ognon Street, and other streets were blocked, so that no one could get out, so the order was given to open fire. Bullets from machine guns and rifles began to chip the walls and shatter the windows; advancing slowly, Polish legionnaires threw hand grenades at houses and barred doors. Cries of terror arose from inside the houses; and some leaped into the open and were instantly slain.

With shouts of triumph, the soldiers continued to drop their bombs.

When the populace was utterly terrified, when they had had ample examples of what to expect in case of resistance, the officers gave the order to cease fire and sent patrols into the houses. The orders were issued from the Teatro Comunale, where the high command had placed its headquarters. The patrols advanced from house to house, breaking down the doors, penetrating the interior and throwing everything they contained into the street. In the wealthier houses, the inhabitants were ordered to stand against the wall with their hands up, while the officers searched them for money, jewels or other valuables. Here and there, the soldiers were not satisfied with looting: the sight of some beautiful woman kindled their desires; husbands, brothers, sons were tied up and in their presence women were raped by the soldiery. And as if that weren't enough, soldiers and officers were gripped by an insane lust for blood; there were babies stabbed in their cradles in the presence of their mothers, men struck down with rifle butts, women disemboweled with bayonets. Outside, in the streets, a crazed mob clamored for more blood, more loot.

At the gates of the district, military trucks stood still on which the drunk and sweaty soldiers loaded the looted household goods, which were then transported to the collection points. Here, the civilian population fought furiously for the division of the booty. Shawled commoners, elegant ladies in furs, street girls, nurses, nuns, teachers, all jostling and screaming to get their share. "Give it to me, Captain!"

"No, me! I want that one!" they screamed. The rich came by carriage, to be able to take more stuff. Jewish shops were emptied of all clothing, food supplies, all kinds of merchandise. An interminable column of loaded trucks came out of the gates of the Jewish quarter, crossing each other with one of empty trucks that entered. On the second day, when the looting was over, the high command gave the order to set fire to the Jewish Quarter. Now the trucks carried petrol drums taken from Jewish shops the day before. The walls of Jewish homes were sprinkled with it; mattresses, blankets, petrol-soaked straw sacks were piled up against the doors, so that no one could escape. Then the torches were placed on it.

Shouts of terror arose from inside Jewish homes: "Fry in your own fat!" shouted the soldiers and officers. From homes, Polish legionnaires turned to synagogues and houses of study.

Four officers, each commanding a squad of ten men, entered the Forshtetter synagogue. They tore down the curtain in front of the sacred Ark, opened the door and took possession of all the precious objects it contained; they took the silver crowns, the handles of the scrolls, the chalices and the candlesticks. They stuffed all these things into a sack along with the silk and velvet hangings of the holidays.

The bare scrolls were thrown to the ground, trampled on, and soiled.

When the interior of the synagogue was entirely devastated, the soldiers threw several hand grenades into the stripped Ark, then set fire to the ancient building. Two thirteen-year-old boys who lived on Synagogue Street, David Reubenfeld and Israel Feigenbaum, ran into the burning synagogue and picked up the scrolls of the Law lying on the floor. With those sacred objects in their arms they ran out, but at the door of the synagogue they were shot down by Polish legionaries. A similar fate had the other synagogues and study houses in the neighborhood. The officers took away all the silver items from the temple on Shulkev Street.

Some, not satisfied with the looting, with drunken frenzy, gave free rein to their hatred and their contempt for the Jewish religion. They tore off the coverings of the Ark, wrapped them around their heads like turbans, and danced around, rocking back and forth in parody of the praying Jews, amid the laughter and banter of the soldiers. When they had had enough fun, the officers ordered the floor to be unnailed, gasoline poured into the foundation, and the whole thing set on fire. In another prayer house on Synagogue Street, some Jews wrapped themselves in shrouds, covered their heads with prayer shawls, and began to recite the prayers of the dying by beating their breasts. The doors were closed and barred from the outside, and the building set on fire. The Jews continued to pray until the flames reached the prayer shawls. An officer, seeing the spectacle from the window was horrified. He opened a side door and shouted for the Jews to come out. But in the din, in the groans, in the confusion it was not heard, and the Jews perished in the flames. The looting and destruction of the Jewish quarter lasted three days and nights. The soldiers murdered and ravaged; houses and synagogues were destroyed by flames; the city firefighters did not move from the barracks. On the fourth day the terrified Jews, weakened by the catastrophe, crawled out of the rubble and began looking for their dead. The charred corpses were wrapped in prayer shawls, the unidentified remains were placed in jars, to be able to give them a decent burial. From the still smoking ruins, fragments of sacred furnishings and pieces of parchment that had once been scrolls of the Law were placed in other earthen jars to be buried as well. Seventy-two dead were lined up under prayer shawls, and among them sobbing men and screaming women sought their loved ones. All the Jews of the city gathered for the collective funeral of the martyrs and of the desecrated and destroyed scrolls. Among the thousands of men and women in mourning, a figure in a light blue uniform stood out: it was Felix Feldblum, officer of the Polish Legion, fighter for the freedom of Poland and already a believer in its messianic future.

(Excerpt from Israel J. Singer, The Ashkenazi brothers, Milan, Longanesi, 2004)

The novel in a nutshell

One of the masterpieces of 20th century literature in the fine translation by Bruno Fonzi.

A long line of emigrants is marching towards the Polish city of Lodz: among them a colorful community of Orthodox Jews who intend to earn a living with the traditional spinning loom. It will be the seed from which large textile industries capable of imposing their goods throughout Europe will be born.

In this small and industrious world, where time is marked by work and religious practices, the two sons of the pious Reb Abraham Hirsch Ashkenazi were born, opposite in character since early childhood: Jakob Bunin, vital and generous, represents the natural force and the joyful instinct to live, while Simcha Meier, introverted and skilled in business, pours his feverish restlessness into entrepreneurship. The parable of existence will lead Jakob to establish himself with his talent as a communicator, while Simcha will touch the peaks of industrial capitalism thanks to a mixture of greed and foresight that overwhelms everything in the name of profit.

Around them, between the end of the 19th century and the First World War, the great events of history unfold and the minor events of a crowd of characters united by a common Jewish spirituality, which leads to generational conflicts, to the point of inducing young to a progressive departure from the tradition of the fathers, up to extreme experiences such as the revolution, the denial of family affections and the affirmation of absolute individualism.

For Jakob and Simcha, separated for almost their entire life, the result is the detachment from Judaism, with the consequent loss of their identity to build a bourgeois respectability. But everything is useless, doomed to failure. Together with capitalism, the destinies of men and women overwhelmed by time and history crumble. Of the Ashkenazi brothers, reunited in one last, desperate embrace, there will be nothing left but the infinite vanity of everything.

Israel Joshua Singer recounts the grandiose and ferocious bourgeois epic of Polish Jews in a novel both choral and individual, in the wake of the great nineteenth-century realism but traversed by the anxieties of the twentieth century: a masterful fresco that stands as the Jewish counterpart of "The Buddenbrooks" by Thomas Mann, and which explains why Nobel laureate Isaac Singer said of his beloved brother: "I'm still learning from him and his work."

(Extract from the back cover of theLonganesi edition, Liquid Audiobooks series)