There are no "liberators". Alone, men who free themselves.

Teresio Olivelli

Introduction

We often think of the Resistance as a monolithic phenomenon, without grasping the extraordinary variety of positions and ideal declinations that, in the twenty months between September 1943 and April 1945, supported it by keeping it united in the common desire to free Italy from the Nazi-fascist enemy, to create a free and quite right. Definitely an important role had, for example, the Catholic partisan formations, operating mainly in the Northeast.

Among these, the Green Flames, formations that took their name from green insignia of the uniforms of the Alpini, from whose departments came most of the former soldiers who formed the very first teams. They mainly operated in Bresciano and in the valleys of eastern Lombardy, and in Reggio Emilia, having their roots in social catholicism and collaborating with the most advanced and socially conscious expressions of the local Church. In these parts, the other formations had a much lesser weight, including those organic to the Communist Party.

Frontispiece of «the rebel» - Homepage site of the rebel

Frontispiece of «the rebel» - Homepage site of the rebelAs the historian Rolando Anni points out, the characteristic of the liberation movement in these areas lay precisely in the strong presence of Catholics. In the Green Flames, the proselytizing of the various parties, and therefore the debate in a strictly political sense, was banned, because it was considered a cause of divisions and therefore harmful with respect to the primary task of the struggle against the Germans and the fascists, which required a strong unity of purpose. The movement, however, also welcomed solicitations from the various experiences of historical anti-fascism. Key figure of the entire movement was that of Teresio Olivelli, at least until the date of his arrest in April 1944. Linked to the foundation and activity of the clandestine newspaper "the rebel", Olivelli embodied the most radically spiritual and revolutionary soul of the Green Flames: cultivator of a dream of moral renewal of Italian society that eliminated the possibility of a return to fascism from the very beginning.

The birth

When, on September 8, 1943, General Badoglio announced the armistice between Italy and the Anglo-American Allies, the nation found itself lost, without a clearly identified enemy to fight against, without a strategy. THE Germans were already taking up most of theNorthern Italy: now, from allies they had become enemies. Those who were not caught in the barracks, unarmed and locked up in a train destined for Germany, threw away their uniform in order to save themselves and joined the ranks of the stragglers. Meanwhile, Mussolini had been evacuated from the prison on the Gran Sasso and placed at the head of a puppet government headed by the Nazis. On the one hand, therefore, the Italian Social Republic of Salò; on the other, the Badoglio government and the Allies. Who to side with? Who to stay with?

In the Brescia area, before the Green Flames could arise and actively operate, it took some time. In the Upper Valcamonica, immediately after 8 September, there was a continuous gathering of men in the huts, far from the centers where Germans and Fascists had begun their forced enlistments and roundups. In the city, on the other hand, the men of the National Liberation Committee representing the political parties had met in the crypt of the Old Cathedral to organize the armed resistance. The first formations of partisans - the "rebels", as the people called them - immediately began to climb above Sonico and Corteno, in Bienno, in Croce di Marone, on the Colle di San Zeno, at the foot of Monte Guglielmo, in Polaveno, in Bovegno, Marmentino, Bagolino, Anfo to escape the roundups and arrests. However, the various groups scattered throughout the territory began to operate in an organized manner only in October, when the first contacts were made to establish one broad and unified formation that he understood them all. In those days the house of Astolfo Lunardi became a kind of headquarters of the Resistance: young people went there to take orders, and from there the directives for the city and the province departed.

In November, Lieutenant of the Alpini Gastone Franchetti (nom de guerre "Fieramosca”) Took the initiative to organize the first operational brigades in the valleys. Together with Rino Dusatti and other young people, he got in touch with the anti-fascists who gravitated around the clandestine paper "Brescia Free(The first issue, mimeographed, was distributed in the city on November 19) and at the oratory of the Philippine Fathers of Peace. The idea garnered a fair consensus.

November 30th, in the home of the engineer Mario Piotti, a meeting was held between the main exponents of the partisan movement from Brescia, Trento, Milan, Sondrio, Padua, Belluno, Lecco and Como; on that occasion the Green Flames were born and the celebrated was drawn up Regulation. Among the participants in the meeting was also Teresio Olivelli, second lieutenant of the Alpine troops returning from the tragic Russian campaign recently escaped from the lager of Markt Pongau (near Salzburg, in the Austria ofAnschluss), who, after a brief passage from Udine, had moved to Brescia. The three battalions operating in the valleys were also officially constituted - the Valcamonica, the Valsabbia and the Valtrompia - and each was assigned a commander - respectively, Ferruccio Lorenzini, Giacomo Perlasca, Peppino Pelosi. The general command was, however, entrusted to the Alpine general Luigi Masini (nom de guerre "Fiori").

The first actions

The Green Flames were recognized by CLNAI (Committee of National Liberation Upper Italy) as autonomous apolitical organizations after a confrontation between Enzo Petrini and Ferruccio Parri in Milan in December 1943. The beginnings were, however, rather confused and hesitant, dominated by a substantial one lack of strategy and guided by intuition when not from improvisation. Fortunately, the influence of Teresio Olivelli and the military organization of Romolo Ragnoli, commander first of the brigades and then of the divisions in Valle Camonica, made themselves felt.

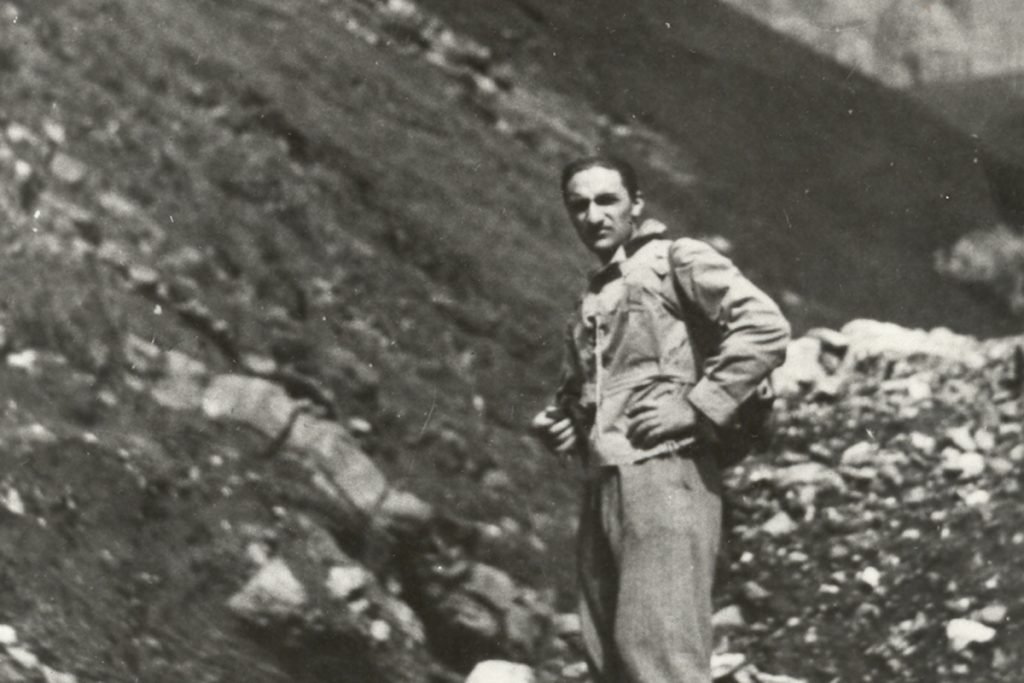

Partisans in the mountains (1944) | © Historical archive of the Brescia Resistance and the contemporary age

Partisans in the mountains (1944) | © Historical archive of the Brescia Resistance and the contemporary ageThe long winter of '43 -'44, despite the commitment and enthusiasm, it was tragic. First for the sacrifice of Ferruccio Lorenzini, who, immediately installed in Valcamonica, was captured by the Republican National Guard, publicly beaten, tied hand and foot, put to the sedan and then shot. In January, then, there were two waves of arrests that hit leading figures of the newly formed Brescia Resistance: Father Carlo Manziana, Peppino Pelosi, Andrea Trebeschi, Astolfo Lunardi, Ermanno Margheriti, Mario Bendiscioli, the Salvi brothers, Don Vender, Giacomo Perlasca and Mario Bettinzoli. Lunardi and Margheriti, in particular, were almost immediately shot, which outraged and moved many partisans and civilians.

The death of Teresio Olivelli

Teresio Olivelli was instead arrested in Milan on April 27, 1944. Imprisoned and deported in Flossenburg lager and then in that of Ersbruck, he died on 17 January 1945 as a result of the beatings received for trying to defend a fellow prisoner beaten up by a kapo. Together with him he was also taken Rolando Petrini, aged only 24, who died of starvation in Mauthausen a year later. On 20 May it was the turn of Don Battista Picelli, who was only 29 years old; fell into an infamous trap of the infamous Banda Marta, he was brutally beaten and killed while carrying out his mission of care of souls even among the partisan formations of the middle Valcamonica.

The recovery

Between September and October 1944 the round-ups and shootings became even more pressing. This time, however, the Green Flames resisted and scored some unexpected successes. In Alta Valcamonica the partisans even managed to implement a democratic experiment: the podestà of Ponte di Legno was removed, the election of the municipal council. A reference figure was the young parish priest of the town, Don Giovanni Antonioli, a fervent anti-fascist. Other municipalities in the Upper Valley followed this example.

In general, the experience of those months

it had pushed the Green Flames to structure themselves in a more strictly military sense.

In fact, despite the winter months they were a time of stagnation of activities

rebellious, the partisan movement did not enter into crisis like the year

previous one.

The battles of Mortirolo

In this scenario, the only two took place between February and May 1945, in the area of the Mortirolo Pass pitched battles of the Brescia Resistance, among the most important of the war of liberation. The first took place between 22 and 27 February 1945, a period during which the fascists of the 1st Legion assault “M. Tagliamento ”tried several times to encircle and overwhelm the partisans, without success. On March 23, then, just over two hundred Green Flames were attacked by over two thousand Fascist soldiers of the “Tagliamento”, who repeatedly attempted to break through the passes. The hostilities were supported by the German artillery, which fired at the partisan positions with cannons. The fighting lasted, on several occasions, until 1 May 1945, when the Germans signed the unconditional surrender in the hands of the Allies.

Partisans in the city (1945) | © Historical archive of the Brescia Resistance and the contemporary age

Partisans in the city (1945) | © Historical archive of the Brescia Resistance and the contemporary age The underground press

From the very beginning, what would later become the most characteristic element of the Catholic Resistance had supported the entire organization of the Green Flames: the underground press. The objectives it set itself were mainly two: inform the combatants on the most important war events and educate readers to confrontation and democratic dialogue, proposing ideal, cultural and moral reflections (but also provocations) aimed at the "free consciences" of Italians.

Of course, observed with today's eyes, these mimeographed or precariously printed sheets, full of typos and sometimes overflowing with rhetoric they do not seem to have a central role in the partisan struggle; however, the news thickly accumulated in the narrow space of the pages, the full-bodied and often not too easy to read articles communicate an overwhelming eagerness to express oneself and an urgent need to explain everything that was happening.

The most important periodical is undoubtedly "the rebel". Founded in Brescia in 1944 (but printed between Milan and Lecco) by Teresio Olivelli, Laura Bianchini, Claudio Sartori, don Giuseppe Tedeschi, Rolando and Enzo Petrini, Franco Salvi, Claudio Sartori, don Giuseppe Tedeschi, and many others, the newspaper was the l official organ of the Brescia "Green Flames" and was immediately distributed throughout Lombardy in a very high number of copies (15.000 for each number).

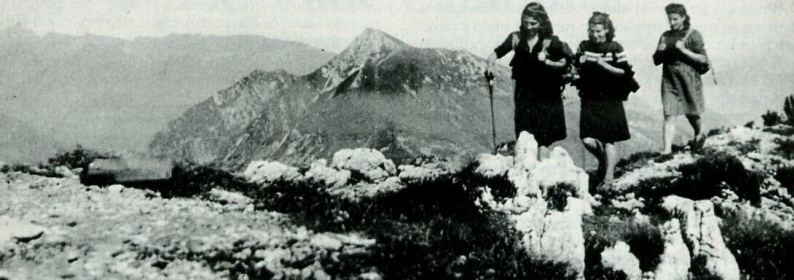

Partisan relays on the Corna Blacca (1944) | © Historical archive of the Brescia Resistance and the contemporary age

Partisan relays on the Corna Blacca (1944) | © Historical archive of the Brescia Resistance and the contemporary ageFrom the very beginning, the project of «the rebel» presented itself as very ambitious: it was widespread thanks to one dense network of volunteers, collaborators and supporters in the city, in the Brescia and Bergamo valleys, in the Lombard plain and in the main centers of Lombardy and Emilia; it was also often reprinted locally. At first read primarily for news, it soon became the real main news outlet, which replaced the periodicals of the regime, which were more concerned with hiding failures than communicating news.

The prevailing communicative intention in the articles of "the rebel" was pedagogical. Even the smallest information, the most irrelevant, performed this function: to bring the reader to become aware of the moral void represented by fascism. From the ideological point of view, two complementary thrusts can be found. On the one hand, that of Olivelli towards one profound and revolutionary innovation of the Italian company; on the other, that more conservative and of a more purely Catholic-democratic matrix, tending to moderate the revolutionary attitude. It will be the latter, slowly, to take over.

Conclusions

The Green Flames, as it was said, did not engage in political proselytism; within the Catholic formations they militated popular, communists, socialists, shareholders, liberals, Badogliani and ordinary citizens. There was, therefore, an extraordinary variety of positions.

Read some of them for a better understanding

steps of the Discussion scheme of a reconstructive program ad

Christian inspiration tracked by Teresio Olivelli:

What we want:

- Freedom:

to think, to express themselves, to organize themselves, to participate in training

of the will of the community.

- Equality: not abstract, but concrete

- (...)

- Work in all its forms

- it will express in society the value of the person and the fulfillment of his

- main political duty. From each, according to his aptitudes, to each

- according to its merits. (...)

What we repudiate:

The dictatorship, the mortifying statism. War as a means of asserting one's rights, both between nations and between classes.

The privilege of birth and gold, the exploitation of man by man. (...)

The forms of capitalist production that make work a commodity and subordinate the activity of the worker to ends not proper to it, making him a proletarian. The anti-Christian division of society into economically privileged classes, the ones disinherited (…).

The real "ideological" glue, alongside the idea that only propaganda against fascism and the occupiers could be tolerated, was the belief that the battle had to take place against fascism, not against the fascists. The dignity of the person, with his or her human rights, prevailed over any distinction of a political or party nature. Repentance, conversion, redemption - founding principles of the Catholic cultural tradition - never ceased to be recognized and preached.

Though some historiography - above all of a Marxist imprint - he often portrayed the activity of the Green Flames as dominated by waiting, substantially immobile waiting for the Allies and strategically oriented not to alienate the political support of moderate and conservative groups after the war, it was some partisans communists (like Giorgio Bocca) to recognize the importance of Catholic formations for the Northeast Resistance. The studies by Dario Morelli and Rolando Anni, which still today constitute the most precise and documented historical reconstruction of all the events that involved the years from '43 to '45 in Brescia and its province, have demonstrated this spontaneous conviction.

Teresio Olivelli's human and spiritual parable, in particular, embodies the search for that profound moral transformation, the only one able to expel fascism forever from the consciences of the Italians, which is the most ambitious goal - and at the same time, the most difficult to achieve - that the Catholic Resistance has bequeathed to future generations, including ours .

To know more

- www.fiammeverdibrescia.it is www.il-ribelle.it: the official sites of the Associazione Fiamme Verdi Brescia with news and historical insights edited by Danilo Aprigliano with the historical supervision of Rolando Anni and Roberto Tagliani;

- D. Morelli, The mountain does not sleep. The Green Flames in the upper Valcamonica (1968), Brescia, Morcelliana, 20152;

- R. Years, History of the Brescia Resistance 1943-1945, Brescia, Morcelliana, 2005.

Article published on 27 April 2020 on The Pitch Blog