«Q

when he was there, the trains arrived on time" is the forte of those who want to underline, perhaps with a sense of nostalgia, the efficiency of the fascist state.

Richard Carr, an English historian, reconstructed the political thought of Charlie Chaplin who, following a trip to our country in 1931, said he was «impressed by the Italian atmosphere», where «discipline and order were omnipresent. Hope and desire seemed in the air." The historian tells how even the director of The Dictator fell into the adage that "the trains arrived on time". But was it really like that?

The myth began to be created in 1924, when the minister Costanzo Ciano began to spread the slogan of "trains on time", an objective to be achieved with rigorous "discipline and regularity of operation".

The need to convey a new image of the Italian railway transport system was part of a more general propaganda plan on the efficiency of the new regime. In particular, we wanted to put an end to the continuous strikes which had given no respite since the years of the Red Biennium and were one of the main perceived causes of disservice. Already in January 1920, Mussolini was riding the wave of demonization of the railway strikes in the columns of his newspaper Il Popolo d'Italia.

During the years between 1922 and 1924, a massive number of layoffs among railway staff was already foreseen among the agendas of the first Mussolini government. For these redundancies, care was taken to choose largely activists and sympathizers of the socialist and communist parties, with the often fictitious motivation of "poor performance". The objective was to eliminate strikes and exercise total control over railway efficiency, a reflection of a more general efficiency of the nation.

Overall, the image that the Italian government wanted to offer abroad was one of great management capacity and good administration. The regime focused with conviction on the railways, considering them an indispensable showcase capable of conveying a vision of fascism that only partially corresponded to the truth.

The increase in the volume of passenger and freight traffic exalted by fascism was in reality a phenomenon that actually concerned the whole of Europe, which experienced, between 1925 and 1930, an extraordinary development of infrastructure.

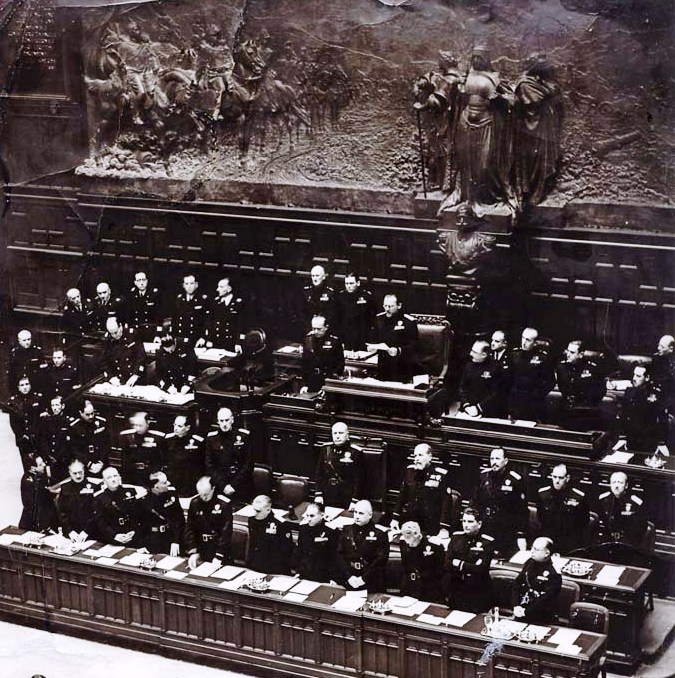

Costanzo Ciano, father of the more famous Galeazzo who married Edda, the Duce's daughter, was count of Cortellazzo and Buccari. He was Minister of Communications from 1924 to 1934 and president of the Chamber of Fasci and Corporations from March to June 1939 when he died.

The Ministry of Communications was specifically established by the regime in 1924, bringing together the navy, post and telegraph services and railways.

The years between 1922 and 1924 are the years of the first Mussolini government and mark the transition between the liberal state and the fascist one, conventionally started with the speech in which the Duce takes responsibility for the Matteotti crime.